Linen 1900 -1910

Lingerie set consisting of cotton knickers and shirt with pink silk ribbons and floral embroidery, circa 1905, Camilla Colombo Collection.

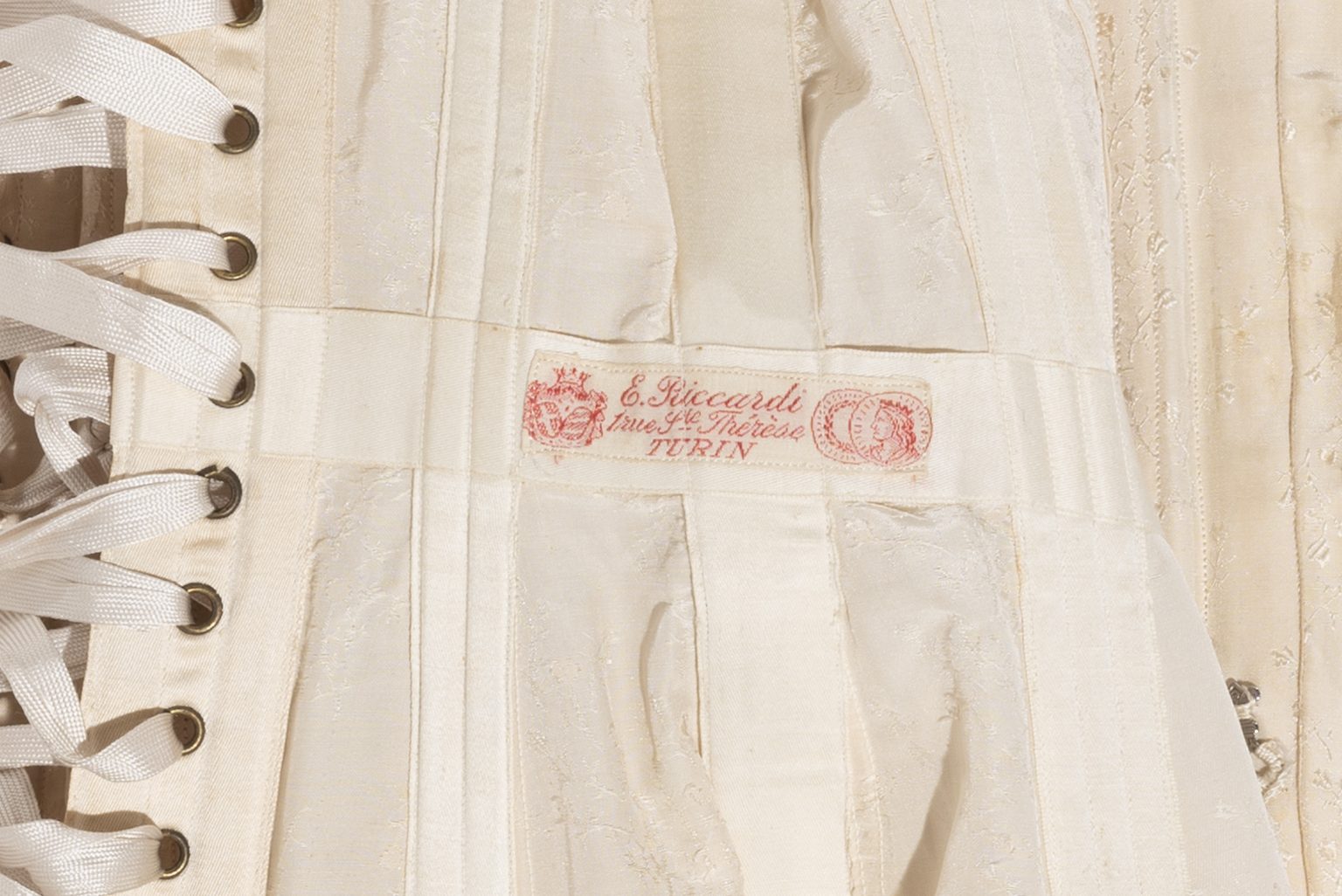

Ivory pink silk corset with small floral motifs and two garters in the centre front, circa 1900-1908, Camilla Colombo Collection.

Details

Historical context

Although worn under layers of clothing and hidden from view, underwear was a fundamental element of clothing in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Once the mere hygienic task of protecting clothes from body odour and perspiration had been overcome – underwear was in fact the only part of daily clothing that was laundered regularly – and the task of modelling the figure had been achieved, linen became a precious display of lace, delicate linen fabrics and silk ribbons in soft pastel shades, with a richness never seen before. There were many different garments that made up the lingerie that a woman had to wear every day at the beginning of the century, and they all contributed to creating the characteristic silhouette of this period, which saw the ideal woman have a very slim waist, a large chest pushed forward, and wide hips pushed back. Wide, knee-length knickers, often completely open in the middle for convenience, were worn over a sleeveless, thigh-length day shirt. On top, the tight corset shaped the body by shifting the body’s volumes. The lingerie was completed by a corset cover, i.e. a short sleeveless blouse, and one or more underskirts, the last of which – far enough from the body not to have to comply with the easy-to-wash rule – was often made of silk. And where mother nature failed, strategically placed ruffles and padding perfected the sculptural work.

Fashion

Women and the corset

The corseted bust accompanied Western women on a daily basis for over three centuries, fulfilling the task of supporting the breasts, but above all of modelling the torso by shifting the volumes to obtain the ideal silhouette according to the fashion of the moment. While 18th-century corsets enclosed the female body in an inverted cone, and 19th-century corsets modelled it in

an hourglass shape, early 20th-century corsets were characterised by a straight frontal splint that stretched downwards, pushing back the pelvis, arching the back and moving the bust forward. This unnatural pose forced women into a sinuous shape composed of two marked curves superimposed, the breast curve extending forwards and the pelvis curve pushed backwards, in an S-curve silhouette. Inès Gâches-Sarraute, a French corset maker and doctor, is credited with the introduction of this type of corset, which she called the abdominal corset. Her aim was to ensure that internal organs were no

longer pushed towards the lower abdomen, as was the case with the hourglass corset, but maintained their natural position, which she claimed was less harmful to women’s health. Whether this model was really less harmful than its predecessors or not, it was destined to be short-lived. The outbreak of the First World War, and the new demands for practicality and freedom of movement, marked the end of the era of the corset. Women could not and would not be caged in by their clothing any longer, and the use of the corset began to decline, first becoming less constrictive during the war, and then transformed into an elastic sheath soon after, as women gained, metaphorically and literally, a new freedom of movement.